Understanding Named Credentials

Synopsis

Named Credentials allow Salesforce developers and administrators to specify the URL of an outbound HTTP call and its required authentication parameters in one definition. By capturing this in a declarative manner, you don’t have to worry about the authentication protocol implementation, endpoint allowlisting, or token storage. Trailblazers can focus on their Flows or Apex code and let the Salesforce platform handle the rest.

The remainder of this article goes into additional detail on the different aspects of this feature set and deepen your understanding. Think of it like a director’s commentary to a movie; not strictly required, but available for those that want a deep dive.

Origin

The Apex programming language has had HTTP callout capability for quite a while, and, in the early years, administrators needed to specify which endpoints can be referenced in callouts by defining Remote Site Settings. This is an allowlisting construct which forced administrators to explicitly take action before code in their org could call out to a remote system. (That notion of explicit action persists to this day, but in a different form.)

The popularity of OAuth caused us to reevaluate this problem space, since OAuth’s browser flow is a multi-step process that is difficult to manage in Apex with a high degree of trust. This combination of factors prompted the team to combine the endpoint definition with built-in authentication protocol support—and thus, Named Credentials was born.

Capabilities

Named Credentials includes many capabilities; what follows is a description of each one.

Auth Protocol and Token Management

Named Credentials handles the handshaking between Salesforce and the remote identity provider or token endpoint. This is more than just a single OAuth implementation; there are multiple variants under the OAuth standard, as well as completely different auth approaches like AWS’s Signature V4, API keys, JWT, and Basic Auth. We keep up with these specs, as well as the ways in which major vendors have chosen to implement them.

We also handle encrypted token storage and refreshing, so your application can wash its hands of that concern and never touch a sensitive value. It’s wise to consider these tokens as “radioactive” and not handle them any more than necessary.

Endpoint Definition and Allowlisting

By defining the target endpoint in a Named Credential, you can allow administrators to adjust it by keeping it out of your code. This gives you more flexibility when it comes to production deployments, keeping your code cleaner and less likely to fail audits.

Furthermore, Salesforce administrators can control which remote endpoints their orgs are allowed to call; this has always been an element of trust supported by the Salesforce platform. But when the endpoint is defined in a Named Credential, this is handled automatically.

Private Routing

Highly regulated industries like financial services and health care often prefer to route network traffic privately so that it doesn’t traverse the public internet. Named Credentials supports this by leveraging Private Connect, which allows integration traffic between a Salesforce org and an AWS account to avoid the internet. Salesforce and AWS have worked together to bridge our networks together to deliver this capability.

Bear in mind there’s no other way to achieve private routing in your callouts besides using a combination of Named Credentials and Private Connect. You define the target endpoint in a Named Credential, and also specify the Outbound Network Connection that should be used to route that call. If you make the callout in “raw” Apex code, it will be routed over the public internet.

Configuration API

While Named Credentials support the Metadata API, this can only be used to move some configurations between orgs. Unfortunately, you can’t use it move any shared secrets like API keys between your orgs, because that would involve retrieving the secret value from the org in clear text (before deploying it to the target org). You also can’t package these secrets, for the same basic reason.

To close this gap, we have a configuration API, available in both Apex and via REST (as a Connect API). You can use this API as a control plane to create and manage credentials, enabling what you might call infrastructure-as-code or policy-as-code. This new API gives you different options to solve these issues, as well as others we haven’t foreseen regarding setup. You can write code against this new API and blend it into your CI/CD pipeline.

Refer to our packaging guide for details on what you can package, and where you’ll need to use the API to close any remaining gaps.

ISV Support

It’s worth reiterating that the configuration API supports creating Named Credentials from Apex code, which is useful for ISVs that want to build a custom setup experience for administrators installing their managed package. We have a developer guide with Apex samples devoted to this topic.

Note that credentials created in this manner are attributed to the namespace of the managed package that created them, but are disabled by default. An administrator needs to explicitly enable them for callouts using a toggle switch.

As of this writing, Apex can only be used to create Named Credentials—not edit or delete them. We plan to address this soon, but when we do, any updated credentials will be left in a disabled state that requires administrators to turn them back on manually. This prevents a nefarious ISV from redirecting their endpoints from a trusted one to one that an administrator hasn’t seen.

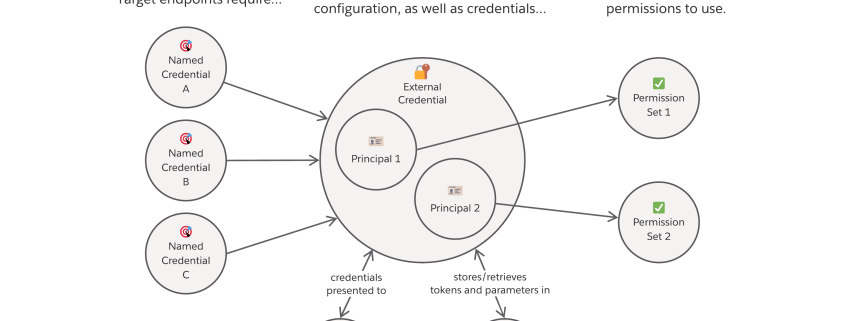

Granular Principals and Permissions

Named Credentials supports robust security in multiple ways. First, explicit access is required to use the Principal in a credential—the identity of the caller in the external system—for a given callout. (AWS also uses the term Principal to represent the same idea.) Many times, this identity is an “integration user” or “service account” that does not correspond to an individual human being. Principals like that typically hold an API key or other secret, for example. The permissions make it explicit that a given User has been granted access to that key/secret—not in its raw form, but usable within the context of a callout. The callout will be blocked if the calling user hasn’t been granted permissions to the Principal.

Users need permissions to make callouts using a certain Principal. It’s similar to how we added the requirement a few years ago that users need explicit permission to run an Apex class. (A key principle for us at Salesforce is that everything is secure by default.)

Additionally, we allow multiple Principals to be associated with a given credential. Service Cloud agents, for example, might have read access to data in a remote system, whereas Service Cloud managers also have the ability to delete records in that external app. If a single User is granted access to multiple Principals for the same credential, there’s a precedence that can be applied to decide which one to use. Essentially, admins set a numerical order using the Sequence Number.

Approximating Record Sharing

The use of different Principals opens the door to external data with different levels of access, almost like record sharing in Salesforce. If a given endpoint can return different results with different user context, we want to enable access that’s as fine-grained as the endpoint allows.

Even though most remote systems only support broader “roles” like “Sales” vs. “Marketing,” major vendors like AWS do in fact offer very fine-grained access controls, and we encourage customers to take advantage of them to the fullest extent possible. That way, the Salesforce “client app” has minimal, optimized access to the remote system. We enable this via support for AWS’s IAM Roles Anywhere, dynamic scopes in OAuth, and more.

Extensible Architecture

This is a robust subsystem with a lot of “headroom” for future growth. We are committed to solving for as many different variations of authentication challenges as we can reasonably support across our many thousands of customers.

Rationale: Why not “roll my own?”

It’s possible for you to write your own Apex code to handle authentication handshakes, but it’s a bad idea. From the security perspective, you’d need to figure out where to store the various tokens securely—but pass it to different user contexts at the right time to perform the callout successfully. It’s easy to mishandle this and create a vulnerability. Other major vendors like Google also encourage developers to use well-debugged libraries to tackle this task.

From the productivity perspective, the less code you have to write and maintain, the better. Let us handle it and stay focused on what’s unique about your application. Why do undifferentiated work?

Expanded architecture: why the change?

In recent years, we’ve expanded the architecture to prepare for future growth and deepened support for other protocols like AWS SigV4, API keys, and JWT with custom claims. We’ve also added a configuration API to make it easier to automate the deployment of credentials across environments.

As we built support for this myriad of options, we came to a point where we could no longer squeeze all the configuration settings for the entire subsystem into one database table. We would’ve needed something like Record Types, but unfortunately that doesn’t exist for metadata objects. Hence, there are multiple objects under Setup you’ll need to configure. Read on for an explanation of the different parts.

Understanding Named Credentials vs. External Credentials, Permissions, and more

One change we made as part of the recent architecture expansion is to capture the endpoint and the authentication details via separate (but related) objects under the Setup menu: a Named Credential, and an External Credential. In the case of OAuth’s common browser flow, you’ll also need an External Auth Identity Provider to specify additional configuration parameters. (More on that below.)

The endpoint is still defined in the Named Credential, which now has a lookup to what we call an External Credential. We moved the authentication configuration to this new object; it holds settings for which protocol you’re using (OAuth, JWT, etc.) and the parameters required to make that callout successfully on your behalf. Separating the two objects allows the same auth config to be used for multiple endpoints. For example, you might authenticate against Google’s OAuth service, and then make calls to both the Google Drive API and the Google Calendar API with the same token.

Aside: External Auth Identity Providers

Developers and system administrators often face hassles when integrating enterprise systems due to those systems exhibiting non-standard behaviors. This is extremely common; many major vendors deviate from the OAuth spec in one way or another. To cope with this issue, we’ve split out OAuth configuration even further into an External Auth Identity Provider with a set of Custom Request Parameters. This allows you to add headers, query string parameters, and more to the handshake with the identity provider.

It’s worth lingering on this point for additional clarity. One reason many widely-used systems do not conform strictly to the OAuth specification is that they’re SaaS apps with an element of multi-tenancy; many customers share the same API and infrastructure. So when an application connects to that API, the API demands that clients specify which tenant they are acting on behalf of—and there any many different ways to do this. Some apps have a Salesforce-style My Domain URL, but others might simply expect a string value in a special header. Unfortunately, the OAuth spec does not cover this, so many vendors handle it in slightly different ways.

Due to this divergence of behavior, you’ll often find that you need to add a custom parameter to the query string or as a specially-named header. This is where Custom Request Parameters are useful; you can add parameters to query, HTTP header, or request body for the token request or refresh request. (Typically, the token request and the refresh request will have matching parameters—but you never know!) You can also add query parameters to the authorize request, which tacks them onto the URL users visit to log into the external system.

You may also need to add headers that are part of the HTTP spec to ensure that the IDP’s endpoint is returning information in the format Salesforce expects (JSON). This end-to-end example uses GitHub to show this in action; you can see all the different parts of the Named Credentials stack working together.

So, to recap: because OAuth is both commonly used but requires non-standard configuration, an External Auth Identity Provider is required to capture the additional configuration. An External Credential has a Lookup to an External Auth Identity Provider to reflect this. If the external system deviates from standards so wildly that configuration parameters aren’t enough to get authentication working, you can still use an Auth Provider along with a custom plugin written in Apex. External Credentials can look up to either an External Auth Identity Provider or an Auth Provider, thus providing the fullest range of solutions.

Generally speaking, we recommend using an External Auth Identity Provider along with Named Credentials to achieve integration via OAuth. External Auth Identity Providers are friendlier when it comes to packaging, and offer slightly stronger security by way of PKCE support and suppressed display of the client secret.

Note: the means by which developers and administrators make callouts has not changed. For example, the syntax used in Apex to refer to a Named Credential is the same—even though we have expanded the underlying architecture.

These objects work together to deliver the benefits of Named Credentials, while also supporting new use cases. We’ll use an extended analogy to explain the different pieces.

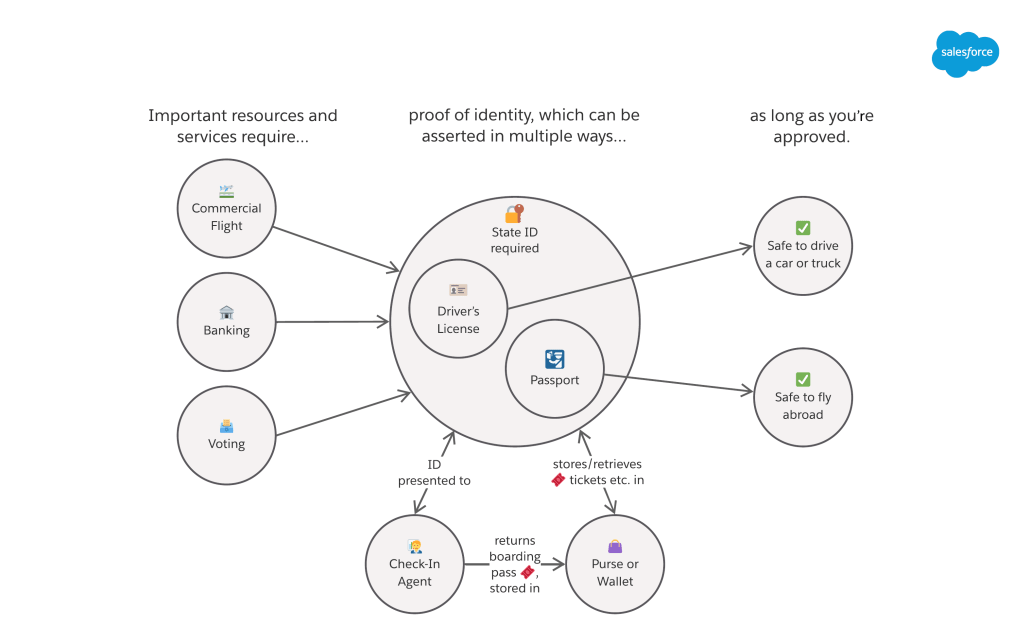

Analogy: Driver’s License and Passport at the Airport

In the United States, most adults present their Driver’s License when asked to verify their identity. This single ID card enables you to access many different resources and services. You include this with your paperwork when opening a bank account. You submit this when registering to vote. And you can use it when checking into a flight at an airport.

Each one of those different resources or services would map to a Named Credential, and you only need one External Credential to access them all. We allow External Credentials to be reused so they don’t have to be duplicated, since doing so is not a best practice from a security standpoint.

Not everyone has a Driver’s License, of course. Only those who’ve passed the test and meet other criteria re: age and physical capability have permission to drive. In Salesforce, this is represented by Permission Sets, and External Credentials are tied to Permission Sets to signal that a given User is allowed to utilize them. (We’ll take a break from the analogy to clarify that this permission check happens at runtime, right before Salesforce makes the HTTP callout on the User’s behalf.)

The convenience of a single ID card is obvious, but we also see potential issues. What does being a safe driver have to do to with traveling by plane—or voting, for that matter? For air travel, it’s better to have a passport. With that form of identification, you can fly to foreign countries and (optionally) save time via programs like Global Entry and TSA PreCheck.

A driver’s license and passport are both state-issued IDs, and there are others like military IDs. So for the sake of this discussion, we might say that U.S. airports have a “State-Issued ID protocol” with its own processes, enforcement, and evolution. This is analogous to an authentication protocol like OAuth 2.0 or AWS’s Signature Version 4. The protocol has an interrelated set of rules and processes that dictate how the verification will work—and they change over time. In the case of U.S. airports, we’re in the middle of a transition from driver’s licenses to the Real ID program (as of this writing). You can think of this as an upgrade to the State-Issued ID security protocol, which deprecates support for simpler forms of identification.

For the time being, travelers can bring either a passport or a driver’s license to the airport to get through security. In Salesforce, we represent this by allowing multiple Principals for a given External Credential, one of which provides more access than the other. (A driver’s license can’t get you into a foreign country, but a passport can.)

Here’s how we might depict this in the example of the airport and other services:

The Moment of Authentication

As you approach the airport, a passport or driver’s license isn’t enough to get you into your seat on the plane: you need a boarding pass. For this discussion, let’s assume you walk up to the counter and check in with an agent. When you give the agent your ID, they authenticate you, checking that the ID is valid (not expired or forged) and represents you (versus someone else). Inherent in this transaction is a request to access a certain resource (a seat on the plane). If all that goes well, they hand you the boarding pass, which will get you access to the desired resource when you’re at the gate.

This critical moment is worth more examination. Most integrations require a two-step process (like the airport) wherein Salesforce presents the credentials (ID card), and in exchange we receive an access token we’ll use down the line. This initial exchange might fail, and the most common reason is that the credentials are invalid or expired. If your ID or passport is expired, the agent check-in desk can’t trust that you are who you say you are—and they won’t give you a boarding pass.

Sidebar: HTTP Error Codes and Token Refreshes

When the callout from Salesforce can’t be authenticated due to invalid or expired credentials, the external system should return an error with a status code of 401. Some systems don’t follow the standards and return a different status code like 400 or 403, which is not correct. A 403 should be reserved to communicate that the identity of the caller is valid, but the external system knows that the caller in question should not be given access to the requested resource.

Interestingly, this is how the Salesforce API works; you may have established your identity correctly, but if you attempt to read a record that you’re not authorized to access, you’ll get a 403 returned. In our airport analogy, I can present a valid ID, but if I purchased a seat in Coach, I won’t be allowed to access the First Class cabin. My identity has noting to do with it; identity is not access. I’m also not allowed to access the cockpit and fly the plane.

When Salesforce receives a 401, we return to the correct endpoint to “refresh” the token by presenting the credentials again—yielding a new token. The Named Credentials subsystem will then attempt the callout again, with an updated token. If Salesforce receives a 403, some other security setting should change in the external system to grant the principal the correct access to the target resource. Until that happens, API callers won’t be able to tell the difference between insufficient access rights and expired authentication.

We recognize that Salesforce administrators often have no control over how external APIs work. Hence, we’ve added a setting to External Credentials called Additional Status Codes for Token Refresh to allow status codes besides 401 to trigger Salesforce to obtain a fresh token. If, for example, the system in question returns a 403, you can simply enter 403 in the text box for that configuration. You can also enter a comma-separated list of multiple response codes; check the documentation on External Credentials for details.

Understanding User External Credentials

Now that you’ve authenticated, you’ve got your boarding pass—which will be critical for the future moment at the gate. In a system integration, Salesforce stores the returned access token securely in the User External Credential object. These tokens expire, and the Named Credentials subsystem handles the refresh process automatically. If Salesforce needs access to the same resource again, we’ll overwrite the old token with the new one.

Note that User External Credential is a data object, not a metadata object. End users who make callouts at runtime will need some access to this object via their Profile or Permission Sets. If you create a new Permission Set, it will have access to this object by default; that’s a convenience we have put in place to save administrators some time and hassle. That said, you can turn that off and grant access in your own way, if you prefer. Our recommendation is to create new, fine-grain Permission Sets for specific external systems that can be bundled into Permission Set Groups. Granting broad access at the Profile level makes it easy to open up “too much” access.

Since User External Credentials are data, they can’t be packaged; this is benefit that avoids the security risks inherent in moving it between environments. To be clear, these sensitive values like access tokens and API keys will not be moved from production environments to sandboxes during a sandbox refresh.

It’s also useful to bear in mind that an in an org with thousands of users, Salesforce may need to store tens of thousands of access tokens. There generally aren’t tens of thousands of metadata records in an org—you’re not likely to have >10,000 Flows or Apex Classes—so we store this as data to make internal operations more efficient.

Using our airport analogy, User External Credential would be analogous to a purse or wallet that holds your boarding pass: don’t forget it! You may need to manage access to this object carefully; this article explains when different levels of access to that object are needed.

Note: If your configuration includes Guest Users, bear in mind they have a unique Profile. If unauthenticated Guest Users are using functionality that makes callouts, you’ll need to grant explicit access to the User External Credential object as part of that Profile. This article in the documentation describes what level of access is needed, depending on the authentication protocol.

Accessing the Resource (Finally!)

You’ve made it to the gate and are ready to board. You present your boarding pass, walk onto the plane, and take your assigned seat. Hooray! You finally made it!

In terms of Named Credentials, Salesforce makes the callout to the target endpoint, and presents the access token along with the request to read a given piece of data or invoke an operation. Access is granted, and we receive the appropriate response.

Certificates

In the analogy above re: a driver’s license or passport, those IDs are similar to a certificate in Named Credentials. A certificate asserts the caller’s identity, but is issued by a trusted, neutral authority separate from both Salesforce and the target external system. Contrast this with a password, which comes with no such additional assurance. My driver’s license was issued by the state of Illinois. A certificate in a system integration might be issued by a company like DigiCert or GlobalSign.

The external system dictates whether or not certificates need to be used, and Named Credentials supports their use when calling the target endpoint. For better or worse, certificates can’t be packaged (as of this writing). This is likely due to the sensitivity in widely distributing a trusted identity. Factor this in when you’re configuring Named Credentials in your org.

Having Trouble with Permissions?

The legacy iteration of Named Credentials did not have any access controls, and we wanted to improve this when we revamped the architecture. In particular, here are some things you should watch out for:

- Callouts will fail if the calling user doesn’t have permissions to the appropriate Principal defined as part of an External Credential. Refer to this Help & Training article for details on how to grant such permissions.

- Callouts will also run into trouble if the calling user does not have access to the User External Credential object, since that object holds the actual access token used with the target endpoint. The section above explains this in more detail, and there’s a special Help & Training article with a complete rundown of how much access is needed based on which authentication protocol is used.

- When a new Permission Set is created, it receives access to the User External Credential object by default. This makes it easier to grant access without worrying about User External Credentials. The object access can, however, be disabled if you prefer to manage your permissions another way.

- Guest Users will always need explicit access to the User External Credential object.

- If a managed package requires you as an administrator to create a particular Named Credential for its use, note that you will need to allowlist the namespace of the package before it can make a callout. Refer to this Help & Training article.

Links and Resources

Configuration info for administrators

- Our starting point in Help & Training

- Our documented explanation of Named Credentials vs. External Credentials

- Our packaging guide (includes information on how to automate what you can’t package)

- Using an API key

- Using OAuth

- Configuring the Browser flow (most common)

- Server-to-server solution with the Client Credentials flow

Code samples and APIs for developers

- Creating credentials via REST

- Creating credentials from Apex

- Our developer guide (meant for ISVs building managed packages)

- A cool Apex recipe

- Reference doc for our Apex classes

Debugging tools

- Send calls to webhook.site to see the headers and request in complete detail. (We can’t log in a highly verbose manner due to compliance concerns.)

- Try Beeceptor to send back mock responses with fake data.